.

Whether you

experienced foster care or adoption or neither,

this story will encourage you

to keep believing that good will find you.

.

.

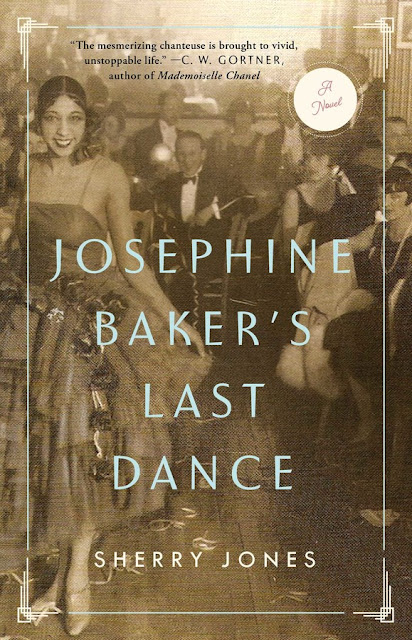

Faded Red Beads: From

an Orphanage to a Disrupted Adoption.

A Story of Courage,

Resiliency and Faith.

by Monica Hargrave

Genre: Nonfiction Inspirational Biography

.

As I began to head upstairs to my bedroom, my adopted father

abruptly asked, “Where have you been?” I responded with, “What

do you mean? I called you at 3:15 p.m. and told you I had a game this

evening.” He said, “No, you did not. I did not talk to you

today!”

I stood there, frozen, thinking, you’re crazy as hell. Mr. O’Neal proceeded to

tell me what my future was going to be, and I didn’t agree with anything he

said. “You will not participate in sports; you will come directly home

from school, cook dinner, clean the house, etc.” As he yelled, I began

plotting my next move. When I tuned in, he said, “You will have no outside

interaction with anyone.” I recall thinking, This is my last day in this

hellhole. It didn’t matter where I ended up, I knew anything had to be better

than this. I wasn’t living at all. His home felt like prison, and I was ready

to be free. This wasn’t about me trying to sneak around and see boys. It was

about a robbed childhood. I didn’t have many answers, but I knew living with

Mr. O’Neal was suffocating. He wasn’t equipped to be an adoptive parent. The

system failed. Providing a roof wasn’t enough.

This story is written to inspire individuals. To move when you don’t have all

the answers about what lies ahead, but you know if you stay where you are, you

will die. To trust your gut and to not copy anyone’s life, you are an original.

It just so happens this story is about a little girl’s journey from an

orphanage to a failed adoption to charting her path forward. Whether you

experienced foster care or adoption or neither, this story will encourage you

to keep believing that good will find you.

Amazon * Apple * B&N * Kobo * Bookbub * Goodreads

.

.

I stood there, frozen, thinking, you’re crazy as hell. Mr. O’Neal proceeded to tell me what my future was going to be, and I didn’t agree with anything he said. “You will not participate in sports; you will come directly home from school, cook dinner, clean the house, etc.” As he yelled, I began plotting my next move. When I tuned in, he said, “You will have no outside interaction with anyone.” I recall thinking, This is my last day in this hellhole. It didn’t matter where I ended up, I knew anything had to be better than this. I wasn’t living at all. His home felt like prison, and I was ready to be free. This wasn’t about me trying to sneak around and see boys. It was about a robbed childhood. I didn’t have many answers, but I knew living with Mr. O’Neal was suffocating. He wasn’t equipped to be an adoptive parent. The system failed. Providing a roof wasn’t enough.

.

When Monica was born, the doctors said, “If she makes

it overnight, she will survive.” Monica spent approximately nine years in

foster care and then ran away from her adoptive family. She strives to empower

women to actively address whatever is holding them back from leading fulfilled

lives. You get one life. Live it. Monica completed her undergraduate studies at

Niagara University and has a masters degree in health administration from

Central Michigan University and a masters in human resources development from

Villanova University. She completed Emory University’s executive coaching

program and coaches women who are unfulfilled in their careers. Monica loves

trying vegan recipes, animals, exercising, and reading James Patterson novels.

She has three furry friends.

Website * Facebook *Instagram * Goodreads

,

Follow the tour HERE for special content and a $20 giveaway!

.

.

.

~~~~~

Thanks so much for visiting fuonlyknew and Good Luck!

For a list of my reviews go HERE.

To see all of my giveaways go HERE.

Author William Hazelgove

Author William Hazelgove